Projeto editorial: Isabel Carvalho.

Coedição: Ang Kia Yee.

Ensaios de José Carlos Marques, ila, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, nuno marques, Salty Xi Jie Ng, ants chua & txting teo, Isabel Carvalho, Lune Loh, Gideonsson/Londré, Ashley ho.

Editorial project: Isabel Carvalho.

Co-edition: Ang Kia Yee.

Essays by José Carlos Marques, ila, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, nuno marques, Salty Xi Jie Ng, ants chua & txting teo, Isabel Carvalho, Lune Loh, Gideonsson/Londré, Ashley ho.

EDITORIAL

De forma a apresentar este número da Leonorana, nós – a equipa editorial – necessitamos de explicar resumidamente as circunstâncias do nosso encontro, as quais, embora estranhas, acabaram por se tornar felizes. Comecemos por aí.

No início deste ano, a Isabel estava prestes a começar uma residência no Nanyang Technological University Centre of Con-temporary Art (NTU CCA) em Singapura, onde tencionara conceptualizar o próximo número da revista Leonorana. No entanto, devido à pandemia global Covid-19, que levou ao encerramento de fronteiras e à impossibilidade de viajar para Singapura, o programa de residências artísticas foi reformulado, adaptado e renomeado como Residencies Rewired [Residências Reconectadas]. Para que não se perdesse a oportunidade, foi lançado um open call para encontrar alguém com base em Singapura que servisse de contacto, à distância, para trabalhar com cada um dos artistas internacionais na prossecução do seu trabalho de investigação artística. Do processo de selecção, Ang Kia Yee foi escolhida para apoiar o trabalho da Isabel. A residência neste novo formato teve início em Dezembro de 2020 e o trabalho começou a ser desenvolvido através de reuniões regulares online entre ambas.

Trabalhámos em estreita colaboração e a bom ritmo. No final de Fevereiro, tínhamos definido as linhas de orientação e os parâmetros para o tema proposto, “ambientes”, assim como os conceitos metodológicos daí provenientes (limites, características, valores e objectivos). E, no final da residência, tínhamos preenchido a nossa grelha editorial e produzido uma lista de possíveis participantes. Obviamente, o número estava longe de estar completo, pelo que concordámos continuar a nossa parceria, com Ang Kia Yee a exercer agora o papel de editora-convidada.

Agora, enquanto escrevemos este editorial e tentamos dar-vos uma ideia do nosso processo, já não nos encontramos num estádio de especulação ou de conceptualização do nosso trabalho editorial. Do material agora recebido, observamos que um certo aspecto sobressai quando lemos os ensaios. Claro que os autores que escolhemos forneceram perspectivas muito diferentes sobre o tema proposto, mas, mesmo na sua diversidade, destacam-se duas abordagens. Perguntamo-nos como as poderíamos compreender. Uma envolve uma ênfase na complexa relação entre o humano e a natureza, começando pela diferenciação ou o falso binarismo entre os dois, que invariavelmente é posto em causa antes de se colocar uma proposta alternativa. Esta alternativa encerra frequentemente um certo tipo de simbiose que ora se revela como já existente (quer estejamos ou não conscientes de tal) quer como desejada. Tal é o caso dos ensaios de nuno marques, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, Isabel Carvalho e Gideonsson/ Londré. A segunda abordagem por nós percebida encontra-se menos preocupada com a diferenciação entre o humano e a natureza. Ao invés, toma como garantida uma espécie de indistinção e foca-se no ambiente enquanto contexto de múltiplas relações, como nos ensaios de Lune Loh, ants chua & txting teo, Salty Xi Jie Ng e ashley ho. Tendo em conta o contexto geográfico dos nossos autores convidados, estas duas abordagens levam-nos a questionar se, sobretudo para os colaboradores de Singapura, os ambientes são raramente entendidos como “naturais”, fazendo das distinções entre o que é “natural” e “não-natural” ou “real” e “artificial” menos cruciais. Claro que estas são apenas observações; não pretendemos, contudo, traduzir a complexidade do que é apresentado numa conclusão redutora, especialmente porque analisar diferenças e agrupar os ensaios parece ser muito menos interessante do que deixar o leitor descobrir a perspectiva que cada um nos dá.

O ensaio de José Marques Que ouvimos quando ouvimos a palavra “ambiente”? propõe uma digressão semântica da palavra “ambiente” e de como foi frequentemente utilizada distintamente das genuínas preocupações ambientais. Em A Fluid Borderless Past: A Photo-Essay, ila move-se através do mar e das suas margens para levantar questões sobre a origem pessoal, a ancestralidade e a memória intergeracional que permanece inscrita no corpo (o qual sabe de forma intuitiva onde pertence e como lá chegar) apesar das fronteiras pelas quais somos governados. Em A Câmera é o Corpo, Ana Vaz dá continuação ao seu trabalho cinematográfico pelo qual explora a arte de criar perspectivas – fundindo o sujeito e o objecto, o olho e a lente – que justificam a realidade de outras formas de vida (humanas e não-humanas) e a sua existência sensorial em determinados ambientes. O leque de poemas de Lune Loh – que compreende Off-Hours/ Post/ Wall of Text/ Murphy’s Law for Interstellar Fissures/ An Empty Barstool is Love (after Pooja Nansi)/ Suiteroom – Take 4 – emerge do meio de um ambiente urbano e aborda como as vidas sociais são configuradas pelas infraestruturas digitais (virtuais), as quais, enquanto prometem uma comunicação e relações mais significativas, se manifestam efectivamente em sentimentos de alienação e solidão. Isabel Carvalho, em As Crianças Intérpretes, analisa versões textuais e imagéticas da fábula da pequena sereia e do seu ambiente aquático para propor que nos pensemos como crianças, não em termos de inocência, mas ao centrarmo-nos como intérpretes e sujeitos do conhecimento que não compreendem as distinções claras entre o humano (sujeito) e o animal (ou a natureza enquanto objecto). Ao propô-lo, pretende questionar as nossas convenções epistemológicas de uma forma que só as crianças sabem bem fazer. The Waterlogged de Gideonsson/Londré consiste em dois textos que correm em paralelo com detalhes altamente descritivos de percepção sensorial, que transmitem a ideia de uma existência humana alterada numa era especulativamente pensada como pantanosa, onde a humidade perturba e emaranha a condição humana. Em Between Here and There, ants chua & txting teo começam por descrever um trabalho em progresso, uma performance colectiva caracterizada pela incerteza do nosso tempo actual de pandemia. A partir deste espaço simultaneamente artístico e mundano, emergem vozes (as suas e aquelas dos seus colaboradores/ companheiros) que comunicam a sua angústia e as suas preocupações mais íntimas, sendo o cuidado comum prioritário. Entretanto, Ang Kia Yee em Our world up in the air reflecte sobre a responsabilidade ambiental e o desejo humano de controlo, que conduz a uma consideração sobre a gravidade tanto como uma característica propiciadora assim como impeditiva da condição humana terrena. Teresa Castro, em Navegar em águas turvas com líquenes, fungos e plantas ruderais, fala de vidas menores na natureza, que se baseiam, como regra, na simbiose mútua, e que problematizam a nossa compreensão sobre o que constitui uma entidade. No processo, ela repara nessas espécies e vidas que emergem ou prosperam em ambientes de toxinas e ruínas. Em What is the weather? Notes on fantasy and risk in working with people, Salty Xi Jie Ng reflecte sobre os princípios de risco e negociação que enformam a sua prática artística socialmente comprometida, em que convida os participantes a co-criarem ambientes que tornam a fantasia, a intimidade e a transgressão possíveis. Em mooing together, nuno marques observa a respiração das mulheres e das vacas na ecopoesia, certamente não só enquanto assunto e metáfora, mas também como uma função fisiológica que configura a produção do texto poético – formando um ambiente onde é possível respirar em conjunto e partilhar o mesmo ar numa solidariedade de inter-espécies. Finalmente, ashley ho, em mountain gaze, dust dances (a score for smudging series: exercise 8), serpenteia através das paisagens europeias e singapurianas e, através da sua prática artística de reapropriação dos materiais de performance, tenta relocar-se a si e à sua arte no âmbito das ansiedades ecológicas.

Com a certeza do prazer que tivemos em preparar esta edição para si, esperamos que goste de deambular pelas suas paisagens montanhosas, pantanosas, húmidas, íntimas e férteis.

EDITORIAL In order to present this issue of Leonorana, we – this editorial team – need to briefly explain the circumstances of how we met, which, however strange, turned out to be happy ones. Let’s start from there.

At the beginning of this year, Isabel was about to start a residency at the Nanyang Technological University Centre of Contemporary Art (NTU CCA) in Singapore, where she had intended to conceptualize the next issue of Leonorana. However, due to the global Covid-19 pandemic, which led to the closing of borders and the impossibility of travelling to Singapore, the artist residency program was reformulated, adapted and renamed as Residencies Rewired. So that the opportunity was not lost, an open call was cast for Singapore-based liaisons for each international artist to work with, at a distance, in pursuit of their artistic research work. From the open call, Ang Kia Yee was chosen to support Isabel’s work. The reimagined residency began in December 2020 and the work began to be developed through regular online meetings between the two.

We worked in close collaboration at a good pace. By the end of February, we had defined the guidelines and parameters for the proposed theme of “environments”, as well as the methodological concepts derived therefrom (limits, features, values and objectives). And by the end of the residency, we had filled up our editorial grid and generated a list of possible contributors. Obviously, the issue was far from completion, so we mutually agreed to continue our partnership, with Ang Kia Yee now taking the role of guest editor.

Now, as we write this editorial and attempt to give you an idea of our process, we are no longer at the speculative or conceptual stage of our editorial work. Of the material that we’ve now actually received, we observe that a certain aspect that stands out when we look at the essays. Of course, the writers we chose provided very different perspectives on the proposed theme, but even in their diversity, two approaches stand out. We wonder how we might understand them. One involves an emphasis on the complex relationship between human and nature, starting from a differentiation or false binary between the two that is invariably called into question before an alternative proposition is set forth. This alternative often involves a certain kind of symbiosis that is either revealed to be already existing (whether we are aware of it or not) or desired. Such is the case of the essays by nuno marques, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, Isabel Carvalho and Gideonsson/Londré. The second approach we perceive is less preoccupied with differentiation between human and nature. Instead, it takes a kind of indistinction for granted and focuses on the environment as a context for multiple relations, as in the essays by Lune Loh, ants chua & txting teo, Salty Xi Jie Ng and ashley ho. Noting the geographical backgrounds of our contributors, these two approaches make us question if, mostly for the collaborators from Singapore, environments are rarely understood as “natural,” making distinctions between what is “natural” and “unnatural”, or “real” and “artificial” less crucial. Of course, these are merely observations; we do not wish to translate the complexity of what is presented here into a reductive conclusion. Especially because analyzing differences and grouping the essays seems much less interesting than letting the reader encounter the perspective that each one gives us.

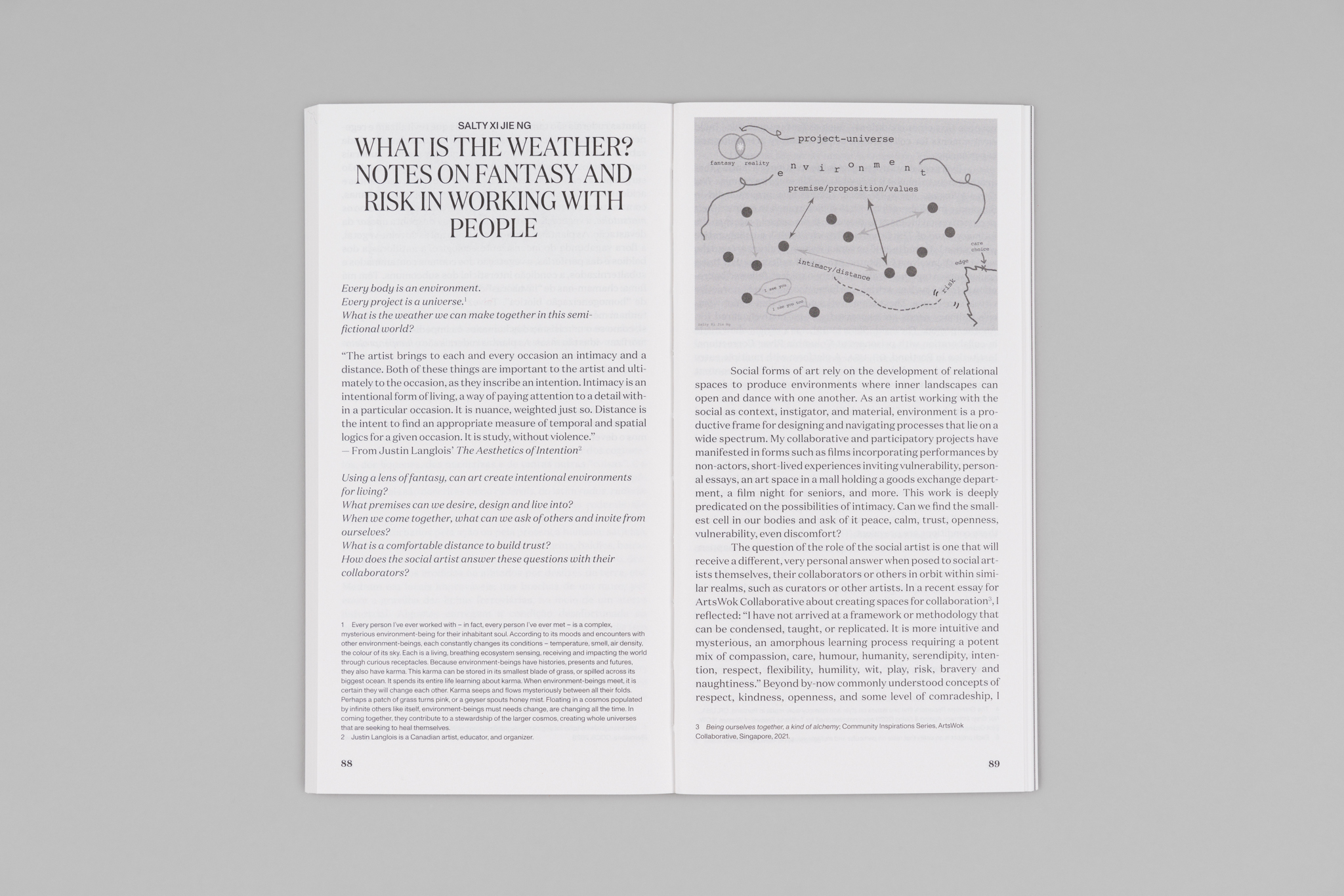

José Carlos Marques’ essay, Que ouvimos quando ouvimos a palavra “ambiente”?, proposes a semantic digression of the word “environment” and how it has often been used as distinct from genuine environmental concerns. In A Fluid Borderless Past: A Photo-Essay, ila moves across the sea and its shores to raise questions about personal origin, ancestry, and intergenerational memory that remains inscribed in the body (which intuitively knows where it belongs and how to get there) despite the borders we are governed by. In A Câmera é o Corpo, Ana Vaz continues her cinematographic work from which she explores the art of creating perspectives – fusing the subject and object, eye and lens – that account for the reality of other forms of life (human and nonhuman) and their sensory existence in given environments. Lune Loh’s suite of poems – comprising Off-Hours / Post / Wall of Text / Murphy’s Law for Interstellar Fissures / An Empty Barstool is Love (after Pooja Nansi) / Suiteroom – Take 4 – emerges in the middle of an urban environment and dwells upon how social lives are shaped by digital (virtual) infrastructures which, while promising more meaningful communication and relationships, actually manifest as feelings of alienation and loneliness. Isabel Carvalho, in As Crianças Intérpretes, analyses textual and image versions of the little mermaid’s fable and its aquatic environment to propose that we think of ourselves as children, not in terms of innocence, but by centring ourselves as interpreters and subjects of knowledge that do not perceive clear distinctions between the human (subjects) and the animal (or nature, as object). In doing so, she questions our epistemological conventions in ways that only children can. The Waterlogged by Gideonsson/Londré consists of two parallel texts with highly descriptive details of sensorial perception which convey humanity’s changed existence in a speculative wetland era where wetness troubles and entangles the human condition. In Between Here and There, ants chua & txting teo start from a work-in-progress, a collective performance characterized by the uncertainty of our current time of the pandemic. From this simultaneously artistic and worldly space, voices emerge (theirs and those of their collaborators/companions) that communicate their anguish and most intimate concerns, with communal care as priority. Meanwhile Ang Kia Yee, in Our world up in the air, mulls upon environmental responsibility and the human desire for control, which leads her to a consideration of gravity as both an enabling and disabling feature of the Earthly human condition. Teresa Castro, in Navegar em águas turvas com líquenes, fungos e plantas ruderais, speaks to minor lives in nature which are predicated upon mutual symbiosis as a rule, lives which trouble our understanding of what constitutes an entity. In the process, she alights upon those species and lives which emerge out of or thrive within environments of toxins and ruins. In Salty Xi Jie Ng’s What is the weather? Notes on fantasy and risk in working with people, she reflects upon the principles of risk and negotiation which inform her socially-engaged artistic practice, where she invites participants to co-create environments that make fantasy, intimacy and transgression possible. In mooing together, nuno marques observes the breathing of women and cows in ecopoetry, certainly as a subject and metaphor, but also as a physiological function shapes the very production of the poetic text — forming an environment where it is possible to breathe together and share the same air in interspecies solidarity. Finally, ashley ho, in mountain gaze, dust dances (a score for smudging series: exercise 8), meanders across European and Singaporean landscapes and then through her artistic practice of re-appropriation of performance materials, attempting to relocate herself and her art within ecological anxieties.

Assured of the pleasure we had preparing this issue for you, may you enjoy wandering through the mountainous, swampy, humid, intimate and fertile landscapes.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎

Coedição: Ang Kia Yee.

Ensaios de José Carlos Marques, ila, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, nuno marques, Salty Xi Jie Ng, ants chua & txting teo, Isabel Carvalho, Lune Loh, Gideonsson/Londré, Ashley ho.

Editorial project: Isabel Carvalho.

Co-edition: Ang Kia Yee.

Essays by José Carlos Marques, ila, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, nuno marques, Salty Xi Jie Ng, ants chua & txting teo, Isabel Carvalho, Lune Loh, Gideonsson/Londré, Ashley ho.

EDITORIAL

De forma a apresentar este número da Leonorana, nós – a equipa editorial – necessitamos de explicar resumidamente as circunstâncias do nosso encontro, as quais, embora estranhas, acabaram por se tornar felizes. Comecemos por aí.

No início deste ano, a Isabel estava prestes a começar uma residência no Nanyang Technological University Centre of Con-temporary Art (NTU CCA) em Singapura, onde tencionara conceptualizar o próximo número da revista Leonorana. No entanto, devido à pandemia global Covid-19, que levou ao encerramento de fronteiras e à impossibilidade de viajar para Singapura, o programa de residências artísticas foi reformulado, adaptado e renomeado como Residencies Rewired [Residências Reconectadas]. Para que não se perdesse a oportunidade, foi lançado um open call para encontrar alguém com base em Singapura que servisse de contacto, à distância, para trabalhar com cada um dos artistas internacionais na prossecução do seu trabalho de investigação artística. Do processo de selecção, Ang Kia Yee foi escolhida para apoiar o trabalho da Isabel. A residência neste novo formato teve início em Dezembro de 2020 e o trabalho começou a ser desenvolvido através de reuniões regulares online entre ambas.

Trabalhámos em estreita colaboração e a bom ritmo. No final de Fevereiro, tínhamos definido as linhas de orientação e os parâmetros para o tema proposto, “ambientes”, assim como os conceitos metodológicos daí provenientes (limites, características, valores e objectivos). E, no final da residência, tínhamos preenchido a nossa grelha editorial e produzido uma lista de possíveis participantes. Obviamente, o número estava longe de estar completo, pelo que concordámos continuar a nossa parceria, com Ang Kia Yee a exercer agora o papel de editora-convidada.

Agora, enquanto escrevemos este editorial e tentamos dar-vos uma ideia do nosso processo, já não nos encontramos num estádio de especulação ou de conceptualização do nosso trabalho editorial. Do material agora recebido, observamos que um certo aspecto sobressai quando lemos os ensaios. Claro que os autores que escolhemos forneceram perspectivas muito diferentes sobre o tema proposto, mas, mesmo na sua diversidade, destacam-se duas abordagens. Perguntamo-nos como as poderíamos compreender. Uma envolve uma ênfase na complexa relação entre o humano e a natureza, começando pela diferenciação ou o falso binarismo entre os dois, que invariavelmente é posto em causa antes de se colocar uma proposta alternativa. Esta alternativa encerra frequentemente um certo tipo de simbiose que ora se revela como já existente (quer estejamos ou não conscientes de tal) quer como desejada. Tal é o caso dos ensaios de nuno marques, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, Isabel Carvalho e Gideonsson/ Londré. A segunda abordagem por nós percebida encontra-se menos preocupada com a diferenciação entre o humano e a natureza. Ao invés, toma como garantida uma espécie de indistinção e foca-se no ambiente enquanto contexto de múltiplas relações, como nos ensaios de Lune Loh, ants chua & txting teo, Salty Xi Jie Ng e ashley ho. Tendo em conta o contexto geográfico dos nossos autores convidados, estas duas abordagens levam-nos a questionar se, sobretudo para os colaboradores de Singapura, os ambientes são raramente entendidos como “naturais”, fazendo das distinções entre o que é “natural” e “não-natural” ou “real” e “artificial” menos cruciais. Claro que estas são apenas observações; não pretendemos, contudo, traduzir a complexidade do que é apresentado numa conclusão redutora, especialmente porque analisar diferenças e agrupar os ensaios parece ser muito menos interessante do que deixar o leitor descobrir a perspectiva que cada um nos dá.

O ensaio de José Marques Que ouvimos quando ouvimos a palavra “ambiente”? propõe uma digressão semântica da palavra “ambiente” e de como foi frequentemente utilizada distintamente das genuínas preocupações ambientais. Em A Fluid Borderless Past: A Photo-Essay, ila move-se através do mar e das suas margens para levantar questões sobre a origem pessoal, a ancestralidade e a memória intergeracional que permanece inscrita no corpo (o qual sabe de forma intuitiva onde pertence e como lá chegar) apesar das fronteiras pelas quais somos governados. Em A Câmera é o Corpo, Ana Vaz dá continuação ao seu trabalho cinematográfico pelo qual explora a arte de criar perspectivas – fundindo o sujeito e o objecto, o olho e a lente – que justificam a realidade de outras formas de vida (humanas e não-humanas) e a sua existência sensorial em determinados ambientes. O leque de poemas de Lune Loh – que compreende Off-Hours/ Post/ Wall of Text/ Murphy’s Law for Interstellar Fissures/ An Empty Barstool is Love (after Pooja Nansi)/ Suiteroom – Take 4 – emerge do meio de um ambiente urbano e aborda como as vidas sociais são configuradas pelas infraestruturas digitais (virtuais), as quais, enquanto prometem uma comunicação e relações mais significativas, se manifestam efectivamente em sentimentos de alienação e solidão. Isabel Carvalho, em As Crianças Intérpretes, analisa versões textuais e imagéticas da fábula da pequena sereia e do seu ambiente aquático para propor que nos pensemos como crianças, não em termos de inocência, mas ao centrarmo-nos como intérpretes e sujeitos do conhecimento que não compreendem as distinções claras entre o humano (sujeito) e o animal (ou a natureza enquanto objecto). Ao propô-lo, pretende questionar as nossas convenções epistemológicas de uma forma que só as crianças sabem bem fazer. The Waterlogged de Gideonsson/Londré consiste em dois textos que correm em paralelo com detalhes altamente descritivos de percepção sensorial, que transmitem a ideia de uma existência humana alterada numa era especulativamente pensada como pantanosa, onde a humidade perturba e emaranha a condição humana. Em Between Here and There, ants chua & txting teo começam por descrever um trabalho em progresso, uma performance colectiva caracterizada pela incerteza do nosso tempo actual de pandemia. A partir deste espaço simultaneamente artístico e mundano, emergem vozes (as suas e aquelas dos seus colaboradores/ companheiros) que comunicam a sua angústia e as suas preocupações mais íntimas, sendo o cuidado comum prioritário. Entretanto, Ang Kia Yee em Our world up in the air reflecte sobre a responsabilidade ambiental e o desejo humano de controlo, que conduz a uma consideração sobre a gravidade tanto como uma característica propiciadora assim como impeditiva da condição humana terrena. Teresa Castro, em Navegar em águas turvas com líquenes, fungos e plantas ruderais, fala de vidas menores na natureza, que se baseiam, como regra, na simbiose mútua, e que problematizam a nossa compreensão sobre o que constitui uma entidade. No processo, ela repara nessas espécies e vidas que emergem ou prosperam em ambientes de toxinas e ruínas. Em What is the weather? Notes on fantasy and risk in working with people, Salty Xi Jie Ng reflecte sobre os princípios de risco e negociação que enformam a sua prática artística socialmente comprometida, em que convida os participantes a co-criarem ambientes que tornam a fantasia, a intimidade e a transgressão possíveis. Em mooing together, nuno marques observa a respiração das mulheres e das vacas na ecopoesia, certamente não só enquanto assunto e metáfora, mas também como uma função fisiológica que configura a produção do texto poético – formando um ambiente onde é possível respirar em conjunto e partilhar o mesmo ar numa solidariedade de inter-espécies. Finalmente, ashley ho, em mountain gaze, dust dances (a score for smudging series: exercise 8), serpenteia através das paisagens europeias e singapurianas e, através da sua prática artística de reapropriação dos materiais de performance, tenta relocar-se a si e à sua arte no âmbito das ansiedades ecológicas.

Com a certeza do prazer que tivemos em preparar esta edição para si, esperamos que goste de deambular pelas suas paisagens montanhosas, pantanosas, húmidas, íntimas e férteis.

EDITORIAL In order to present this issue of Leonorana, we – this editorial team – need to briefly explain the circumstances of how we met, which, however strange, turned out to be happy ones. Let’s start from there.

At the beginning of this year, Isabel was about to start a residency at the Nanyang Technological University Centre of Contemporary Art (NTU CCA) in Singapore, where she had intended to conceptualize the next issue of Leonorana. However, due to the global Covid-19 pandemic, which led to the closing of borders and the impossibility of travelling to Singapore, the artist residency program was reformulated, adapted and renamed as Residencies Rewired. So that the opportunity was not lost, an open call was cast for Singapore-based liaisons for each international artist to work with, at a distance, in pursuit of their artistic research work. From the open call, Ang Kia Yee was chosen to support Isabel’s work. The reimagined residency began in December 2020 and the work began to be developed through regular online meetings between the two.

We worked in close collaboration at a good pace. By the end of February, we had defined the guidelines and parameters for the proposed theme of “environments”, as well as the methodological concepts derived therefrom (limits, features, values and objectives). And by the end of the residency, we had filled up our editorial grid and generated a list of possible contributors. Obviously, the issue was far from completion, so we mutually agreed to continue our partnership, with Ang Kia Yee now taking the role of guest editor.

Now, as we write this editorial and attempt to give you an idea of our process, we are no longer at the speculative or conceptual stage of our editorial work. Of the material that we’ve now actually received, we observe that a certain aspect that stands out when we look at the essays. Of course, the writers we chose provided very different perspectives on the proposed theme, but even in their diversity, two approaches stand out. We wonder how we might understand them. One involves an emphasis on the complex relationship between human and nature, starting from a differentiation or false binary between the two that is invariably called into question before an alternative proposition is set forth. This alternative often involves a certain kind of symbiosis that is either revealed to be already existing (whether we are aware of it or not) or desired. Such is the case of the essays by nuno marques, Ana Vaz, Teresa Castro, Isabel Carvalho and Gideonsson/Londré. The second approach we perceive is less preoccupied with differentiation between human and nature. Instead, it takes a kind of indistinction for granted and focuses on the environment as a context for multiple relations, as in the essays by Lune Loh, ants chua & txting teo, Salty Xi Jie Ng and ashley ho. Noting the geographical backgrounds of our contributors, these two approaches make us question if, mostly for the collaborators from Singapore, environments are rarely understood as “natural,” making distinctions between what is “natural” and “unnatural”, or “real” and “artificial” less crucial. Of course, these are merely observations; we do not wish to translate the complexity of what is presented here into a reductive conclusion. Especially because analyzing differences and grouping the essays seems much less interesting than letting the reader encounter the perspective that each one gives us.

José Carlos Marques’ essay, Que ouvimos quando ouvimos a palavra “ambiente”?, proposes a semantic digression of the word “environment” and how it has often been used as distinct from genuine environmental concerns. In A Fluid Borderless Past: A Photo-Essay, ila moves across the sea and its shores to raise questions about personal origin, ancestry, and intergenerational memory that remains inscribed in the body (which intuitively knows where it belongs and how to get there) despite the borders we are governed by. In A Câmera é o Corpo, Ana Vaz continues her cinematographic work from which she explores the art of creating perspectives – fusing the subject and object, eye and lens – that account for the reality of other forms of life (human and nonhuman) and their sensory existence in given environments. Lune Loh’s suite of poems – comprising Off-Hours / Post / Wall of Text / Murphy’s Law for Interstellar Fissures / An Empty Barstool is Love (after Pooja Nansi) / Suiteroom – Take 4 – emerges in the middle of an urban environment and dwells upon how social lives are shaped by digital (virtual) infrastructures which, while promising more meaningful communication and relationships, actually manifest as feelings of alienation and loneliness. Isabel Carvalho, in As Crianças Intérpretes, analyses textual and image versions of the little mermaid’s fable and its aquatic environment to propose that we think of ourselves as children, not in terms of innocence, but by centring ourselves as interpreters and subjects of knowledge that do not perceive clear distinctions between the human (subjects) and the animal (or nature, as object). In doing so, she questions our epistemological conventions in ways that only children can. The Waterlogged by Gideonsson/Londré consists of two parallel texts with highly descriptive details of sensorial perception which convey humanity’s changed existence in a speculative wetland era where wetness troubles and entangles the human condition. In Between Here and There, ants chua & txting teo start from a work-in-progress, a collective performance characterized by the uncertainty of our current time of the pandemic. From this simultaneously artistic and worldly space, voices emerge (theirs and those of their collaborators/companions) that communicate their anguish and most intimate concerns, with communal care as priority. Meanwhile Ang Kia Yee, in Our world up in the air, mulls upon environmental responsibility and the human desire for control, which leads her to a consideration of gravity as both an enabling and disabling feature of the Earthly human condition. Teresa Castro, in Navegar em águas turvas com líquenes, fungos e plantas ruderais, speaks to minor lives in nature which are predicated upon mutual symbiosis as a rule, lives which trouble our understanding of what constitutes an entity. In the process, she alights upon those species and lives which emerge out of or thrive within environments of toxins and ruins. In Salty Xi Jie Ng’s What is the weather? Notes on fantasy and risk in working with people, she reflects upon the principles of risk and negotiation which inform her socially-engaged artistic practice, where she invites participants to co-create environments that make fantasy, intimacy and transgression possible. In mooing together, nuno marques observes the breathing of women and cows in ecopoetry, certainly as a subject and metaphor, but also as a physiological function shapes the very production of the poetic text — forming an environment where it is possible to breathe together and share the same air in interspecies solidarity. Finally, ashley ho, in mountain gaze, dust dances (a score for smudging series: exercise 8), meanders across European and Singaporean landscapes and then through her artistic practice of re-appropriation of performance materials, attempting to relocate herself and her art within ecological anxieties.

Assured of the pleasure we had preparing this issue for you, may you enjoy wandering through the mountainous, swampy, humid, intimate and fertile landscapes.

︎︎︎ ︎ ︎︎︎